by Jim Goodman

|

| the Wang River running through Lampang |

When the British annexed Lower

Burma in the early 19th century they began organizing the teakwood

business. An excellent, durable

hardwood, with natural oils that make it impervious to water and termites, teak

was an ideal building material.

Vast forests dominated by teak trees existed in both Burma and northern

Thailand. As the British took over

the rest of the country they further developed the trade and extended business

operations into northern Thailand.

British companies leased

forests from local autonomous rulers in the north and set up bases mainly in

Chiang Mai and Lampang, 100 km south.

Lying along the Wang River in a broad plain, Lampang is surrounded by

mountains, then full of forests that were a prime source of teak. But while local authorities were quite

willing to grant foreigners forest concessions, local people did not want to

work in them. So the British

brought in workers from Burma, especially Shan, which not only affected the makeup

of the population, but also introduced new cultural influences. The city today features several

Burmese-style temples, around half of those in northern Thailand.

|

| the walled compound of Wat Lampang Luang |

Lampang is actually the second

oldest city, after Lamphun, in northern Thailand. The younger son of Queen Chamadevi of the recently

established Mon state of Haripunchai, as Lamphun was then called, founded the

city in the 9th century.

Because of the intervening Khuntan Mountains between the two cities.

Lampang enjoyed a great measure of autonomy and indeed, there is scarce mention

of the city in Haripunchai chronicles.

To protect itself from

invasions, Lampang established bastions on all the routes leading into it. When Mengrai of the Kingdom of Lanna

conquered Haripunchai, including distant Lampang, these bastions were

abandoned. But one of them, about

18 km northeast, became the site of Wat Lampang Luang, one of the most

venerated temples in northern Thailand.

Sitting on an artificial mound and surrounded by walls, it looks like a

fortified temple compound.

|

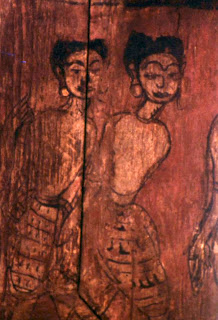

| 18th century mural, Viharn Luang |

|

| 19th century mural, Viharn Luang |

The Buddha himself is said to

have visited the site and left a hair as remembrance, which was then housed in

a shrine that eventually became a chedi,

twice enlarged in the 15th century, that now stands 45 meters

tall. The Viharn Luang in front of

it has a classic Lanna triple roof and an ornate, gilded housing for the main

Buddha image.

|

| 19th century scene, Lampang Luang mural |

The wooden interior walls

feature painted frescoes of the Jataka

Tales, a collection of stories of previous incarnations of the Buddha. Some

of them date from the 18th century, the oldest in northern

Thailand. These are rather crude

portraits, with fewer details and colors than the larger array of early 19th

century murals. Besides veneration

of the Buddha, scenes depict kings at their courts, soldiers assembling for

war, royalty at leisure and rivers full of fish and mythical creatures.

The original mid-15th

century viharn (main prayer hall) has

been replaced since then, though probably in the original style, as have most

of the buildings. But one of them,

Viharn Nam Tam, built in the beginning of the 16th century,

open-sided with a triple roof, has never been rebuilt and is the oldest extant

original temple in the north.

|

| Viharn Nam Tam |

Within Lampang city itself,

the most important temple in the Kingdom of Lanna times was Wat Phra Kaew Don

Tao. Built over a previous Mon

temple in the 14th-15th centuries, it was the original

home of the Emerald Buddha, considered Thailand’s most powerful guardian image.

In 1434 lightning struck a chedi in

Chiang Rai province and revealed a damaged Buddha image. The abbot found that underneath the

exterior stucco was an image of green jade. The King of Lanna wanted it moved to Chiang Mai, but the

elephant carrying it three times detoured to Lampang. So it stayed in Wat Phra Kaew Don Tao until 1468, when King

Tilokaraj removed it to Chiang Mai.

A century later it was taken to Laos and eventually Siamese troops

captured it in Vientiane and took it to Bangkok, where it remains.

|

| Po Thip Chang at Wat Phra Kaew Don Tao |

As the southernmost part of

Lanna, Lampang occasionally suffered when wars between Ayutthaya and Lanna took

place mainly in Lampang province.

Lanna itself began disintegrating in the mid-16th century and

Burmese armies captured Chiang Mai in 1558 with scarcely any resistance. Lampang fell under Burmese rule, too,

but as in the days when it was part of Lanna, Lampang’s administration still

enjoyed a fair measure of autonomy.

There were occasional revolts against bad Burmese governors, but these

didn’t last long. The various

principalities in the north never coordinated their actions.

In the 18th

century, Burmese control began to weaken, even as it revved up for a showdown

with Ayutthaya. In 1732 a Lampang

hunter named Po Thip Chang led an attack on the garrison that had been set up

at Wat Lampang Luang and killed the commander. Such was the politics of the day, though, instead of

organizing a reprisal, the Burmese king confirmed Po Thip Chang as autonomous

ruler of Lampang. In return, until

his death in 1757, the Lampang ruler could be relied upon to aid the Burmese

forces suppressing revolts in other places.

|

| Baan Sao Nak teak house |

Burma conquered and destroyed

Ayutthaya in 1767. But in the

north, sporadic revolts had already been intensifying and now they picked up,

with a little more coordination than previously. The nominal King of Chiang Mai and King Kawila of Lampang, the

second successor to Po Thip Chang, faced with a Lanna devastated by revolts and

reprisals, sandwiched between two more powerful states, decided the best way to

get rid of the Burmese was to agree to ally with and be vassals of Siam.

In 1774 a combined

Siamese-Lanna force expelled the Burmese from Chiang Mai. But after barely surviving a

Burmese counter-attack the following year, Kawila abandoned the city and

removed what remained of the population to Lampang. When Rama I, who had commanded the Siamese troops in the

taking of Chiang Mai, ascended to Siam’s throne in 1782, he appointed Kawila as

King of a restored Lanna.

|

| Baan Sao Nak interior |

But

Chiang Mai was still deserted and the Burmese still in the north. Kawila spent the next couple decades on

expeditions to capture people from northeast Burma to resettle them in

Lanna. He officially

re-established Chiang Mai as Lanna’s capital in 1796 and finally expelled the

last Burmese from Chiang Saen in 1802.

Kawila was one of Lampang’s

‘Seven Brothers,’ or Chao Chet Ton, the dynasty that ruled Lanna until its

final absorption into Thailand.

Another of the original Seven Brothers became prince of Lampang. As it was still several days’ journey

from Chiang Mai to Lampang, he also was a practically autonomous ruler.

|

| the viharn at War Pong Sanuk |

Lampang was the second most

important city in revived Lanna.

Chiang Mai’s population only began exceeding Lampang’s in the mid-19th

century. By then the teak business

had made it one of the two northern cities with a significant foreign

population. The smaller portion of

this was Western, primarily British, some of whom ran the city offices and some

of whom spent many days in the forests supervising the logging. Every December the British community

celebrated Christmas together, alternating between Chiang Mai one year and Lampang

the next. (This became easier

after 1919, when the railway line, which only reached Lampang three years

earlier, was extended to Chiang Mai.)

The other foreign communities

were those who came in with the teak trade—Burmese, Shans and even

Indians. They worked both in the

cities and the forests and some Burmese entrepreneurs became quite wealthy from

the business. One of Lampang’s

most popular attractions today is Baan Sao Nak, the House of Many Pillars,

built in 1895 by a Burmese Mon trader.

|

| Wat Sei Long Muang |

Altogether 116 pillars support

the house’s four connected, Lanna-style buildings, with a Burmese-style

verandah in front. All the

original furniture remains on display—beds, tables, chairs, cabinets full of

lacquer ware, brass and silver bowls, utensils and porcelain, partition

screens, a steam presser for creasing pants and a couple of early 20th

century gramophones.

Other Burmese merchants around

this time sponsored construction of temples for their community. The Burmese have been Theravada

Buddhist at least as long as the Thai, but these temples introduced new

architectural elements distinct from existing Lanna-style structures. The most obvious is the tall, thin,

multi-tiered, ornate tower over the entrances or on the roofs. The shape of the viharn—assembly hall—could also vary, making a tour of Lampang’s

temples interesting for the diversity of shapes and styles.

|

| Wat Chedi Sao |

Built in 1886, Wat Pong Sanuk

rests, like Wat Lampang Luang, on a manmade mound rising above the immediate

neighborhood. Besides a gilded chedi, the compound features a

three-story viharn in an unusual

cruciform shape. The viharn at War Sri Long Muang, completed

in 1912, lies on a horizontal axis, with a very wide roof over a triple

entrance and three-tiered towers on either side of the central one. The building is unlike any other temple

in northern Thailand. And the

central Buddha image, of course, is very much in the Burmese style.

|

| old house on Kad Kokng Ta |

A third Burmese temple from

this period is Wat Sri Chum, in the southern part of the city. U Myaung Gyi, also known as Big Boss,

of mixed Burmese and Shan descent, sponsored its construction and helped pay to

bring in skilled carpenters and craftsmen from Mandalay to build it, which was

completed in 1901. Both the viharn and the smaller ordination hall

feature typical Burmese/Shan roofs, different from the angled, layered roofs of

Thai temples, plus ornamented towers of receding tiers. The viharn

has two side entrances, with elaborately carved filigreed screens just above

the entry staircases.

In 1992 fire consumed the viharn. Basing their work on photographs of the original, Burmese

and Thai artisans tried to build an exact replacement. They got close, but the tower over the

rear entrance is somewhat higher than the original and the exterior walls that

were once an attractive pale yellow are now bright white. A large donation box, a postal

receptacle and a few other small structures now stand between the entry

staircases. And the filigreed

screens above them have been gilded.

Nevertheless, it’s still the finest Burmese temple in Lampang.

|

| horse-carts station in Lampang |

Burmese architectural elements

also crept into the original Lanna-style temples in Lampang. An example is Wat Phra Kaew Don Tao,

where a Burmese tiered tower stands at the entrance, just in front of the old

Mon-style chedi. After this temple, the best known is

Wat Chedi Sao, on the north side of the Wang River. Sao in northern

Thai dialect means ‘twenty’ and that many white chedis with gilded tops stand in the courtyard. It also has, unusually for a Theravada

temple, a statue of a multi-armed Guan Yin, the Mahayana Buddhist Goddess of

Compassion. Wat Koh, on the south

bank of the Wang River, contains buildings in the northern Thai style, but also

a very Burmese-style small shrine in the rear of the compound, full of interior

wall murals.

|

| Kad Kong Ta Street |

The other influence on Lampang

that came out of colonial Burma was that of the British teak wallahs themselves. Lampang’s central clock tower went up

at this time, replicating a feature the British introduced into cities in

Burma. The teak wallahs spent a lot of time in the

forests supervising the work.

Their crews first girdled the trees so that they would die slowly while

still standing and cut them down one to two years later. Trained elephants hauled the logs out

of the forest and shaped them into rafts on the riversides. The logs floated downriver to Bangkok,

staying in the water up to three months.

Coming home out of that

environment, they wanted homes that were spacious and comfortable. Kad Kong Ta, in the northern part of

old Lampang, was a favorite neighborhood and today the old teak wallah homes, largely converted to other

uses like restaurants and lodges, are another of the city’s highlight

attractions. They are a mix of northern Thai and European styles, but in

general so evocative of the teak trade’s heyday that the city chose the

neighborhood as its ‘Walking Street’ on Saturday nights, wherein the street

fills with stalls selling handicrafts and other merchandise, northern foods are

on offer and musicians play Lanna tunes.

|

| horse-cart in the streets of Lampang |

The other enduring legacy of

the British presence is the horse-cart, also previously introduced in Burma and

still in use in Maymyo, or Pwin U Lwin, a hill station near Mandalay. Lampang is the only city in Thailand

one can still take a horse-cart to get around. They ‘re actually cheaper than taxis and a much more interesting

ride.

It’s amazing that they have

survived this long, for the teak wallahs

left a few generations ago and tourism didn’t take off until recent

decades. But now that Lampang is

drawing more attention as an excursion for travelers in northern Thailand, the

future of the horse-cart looks rosy.

They are a throwback to an archaic age, the city’s halcyon days of yore. They are an appropriate vehicle for a

relaxed exploration and enjoyment of the Mon, Lanna, Burmese and British

legacies of Lampang’s fascinating heritage.

|

| the original Wat Sri Chum, 1989 |

*

* *

No comments:

Post a Comment