by Jim Goodman

Mountains in Yunnan rise higher the further northwest you go in the province. They top more than 4000 meters in Dali Prefecture and over 5500 meters near Lijiang. There are other 4000+ peaks in Ninglang County and upper Nujiang, but the biggest of them all lie in Deqin Autonomous Tibetan Prefecture, for most of its territory is geographically the southeastern tip of the Tibetan Plateau. Here the mountains stand over 6000 meters.

The most accessible and popular part of

the prefecture is Shangrila County. It

used to be called Zhongdian until 2001 when, to promote its tourist potential,

the government claimed it was the site of the Shangrila of James Hilton’s famous

novel Lost Horizon and so officially changed its name. With its broad plain, traditional Tibetan

houses, lovely monasteries at Songzhanlin and other places and friendly people,

it certainly appeals as an idyllic escape from the commotion of wherever the

tourists came from.

The Shangrila hype notwithstanding, the village of the novel had a very different setting, in a valley with a triangular-peaked snow mountain towering over one end. Shangrila lies at about 3100 meters and from various points in the county, especially in winter, one can see some snow around the mountains beyond the plain. But they are not very high and to see anything resembling the mountain described in Lost Horizon one has to go further on to Deqin, the next county north.

Not long after leaving Shangrila city, after

passing Napahai Lake, the landscape abruptly changes. From here on the topography is all

mountainous, with no more broad expanse of relatively flat land. The road runs along the higher parts of the

mountain slopes that, in the early 90s during my visits, were largely denuded

of trees, with stray hamlets clinging to the hillsides. Then it descends to

cross the Jinshajiang, the River of Golden Sand that is the moniker for the

Upper Yangzi, and soon pulls into Benzilan, the first major town in Deqin

County.

There were two Benzilans then. In the lower one, the original Tibetan

settlement, the houses lined a ridge overlooking a small plateau that served as

farmland and pastures. The upper one was

the commercial center along the main road, full of shops, hotels and

restaurants catering to travelers on the Shangrila-Deqin route, most of whom

stop here for lunch.

From Benzilan it’s up into the mountains again, where the slopes are high and barren again, although not necessarily due to deforestation. Many gradients are so steep they never supported forests anyway. But streams run down them and there, on modest gradients, Tibetans built their settlements that are patches of green in the otherwise dusty brown landscape. Around 15 km from Benzilan a turn-off takes one a short distance to a dramatic view of a bend in the Jinshajiang, The river makes a loop 2/3 the way around a conical hill protruding from the vertical cliffs on the eastern bank.

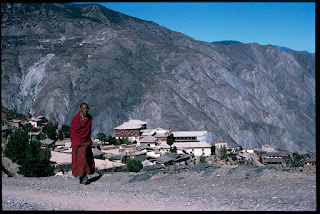

Back to the road, the next stop north is the monastery of Dongzhulin, 103 km north of Shangrila, at an altitude of 3000 meters. The original monastery lay further away from the road and was built in 1667 during the reign of the Kang Xi Emperor, who himself was interested in Tibetan Buddhism. In the 19th century Dongzhulin housed over 900 monks and 12 Living Buddhas (reincarnations of famous lamas). It was here that the French missionary Père Renou disguised himself as a trader and stayed to learn about Buddhism and to speak the local dialect in order to, after he left the monastery, proselytize Christianity among Deqin’s Tibetans.

Dongzhulin became associated with the Tibetan Revolt in 1958, allegedly storing arms for the rebels, and in retaliation government forces leveled the monastery. In 1985 it was rebuilt in its current location, a splendid traditional-style building, four stories high and supported by 82 thick wooden pillars. The ground floor houses large images of various deities like Tsongkhapa, the founder of the Gulugpa (Yellow Hat) monastic order, Avalokitesvar, Manjusri and others. Portraits of celestial beings, demons, benevolent and wrathful deities fill the walls. The 3rd floor features huge images of the Maitreya Buddha, seven meters high, and Sakyamuni, ten meters high. The other floors are for reciting sutras and performing private rituals.

In the early 90s Dongzhulin had about 300

monks and one Living Buddha. There was

also a Buddhist nunnery attached to it.

Nuns follow the same rules as monks, shave their heads, wear robes, recite

sutras, etc, but have the option of staying in the nunnery or living at

home. Most stay in the nunnery across

the road in Shusong.

In the early 90s Dongzhulin had about 300

monks and one Living Buddha. There was

also a Buddhist nunnery attached to it.

Nuns follow the same rules as monks, shave their heads, wear robes, recite

sutras, etc, but have the option of staying in the nunnery or living at

home. Most stay in the nunnery across

the road in Shusong.

From here it’s another 80 km or so to the county capital and halfway there the road runs through a forest and over a pass at 4000 meters. The peak of Baimashan looms to the left of the road. Though only 4292 meters high, it is perpetually covered in snow. The pastures on the edge of the forest are prime yak grazing areas in the summer months. The whole area is a protected nature preserve, home to foxes, deer, leopards and bears. The poplar trees and parts of the pine groves turn yellow in autumn and local species of the maple tree turn red.

From the pass the city is another 35 km through stony hills with thin patches of forest and scarcely any human habitation until just before the city. Formerly called Atuntse, and known to local Tibetans as Jui, Deqin is about half the size of Shangrila and at around 3400 meters a slightly higher altitude. It is sited on slopes that funnel precipitation down to a stream at the lower end of town that eventually empties into the Lancangjiang (Upper Mekong). Most of the buildings then were modern concrete structures, with a quasi-Tibetan style in the upper end neighborhood and no style at all elsewhere.

The only remaining wooden buildings were around the central market, which was about half the size of Shangrila’s but less ethnically diverse, for nearly all the city’s residents are Tibetan. Several shops here and on the main street specialized in Tibetan clothing, crafts and jewelry. City residents and villagers come here to sell off heirlooms, furs and herbs and purchase Tibetan belts, scarves, carpets, woolen cloaks, brocaded silk, fur hats and ornaments of coral, turquoise and silver.

Most Deqin women, though, didn’t seem to

be as fond of wearing traditional clothing as in Shangrila County and when they

did the outfit resembled more the style

of Lhasa, with an ankle-length dress and a long striped apron in front, rather

than the ensemble popular in Shangrila County.

On the whole, they were not as outgoing or engaging as their counterparts

in Shangrila/Zhongdian, but invariably polite and cordial.

Deqin has a mosque, not for Hui but for Tibetan Muslims who converted to Islam when part of Hui-run caravans in the past. The population is overwhelmingly Buddhist, but the devout had to journey to villages beyond the city, as Deqin had no big monastery of its own anymore. During the Qing Dynasty, especially in its last decades, lamas from high-ranking Tibetan families ruled Deqin as their private fief. Around the end of the 19th century two new developments began to challenge their practical autonomy. Under pressure from France, the Qing government allowed French missionaries to proselytize in Tibetan areas. At the same time the government inaugurated a land reform policy in these same areas.

Both of these threatened the lamas’ authority. Land reform would target their own family holdings and conversion to Catholicism would undermine their religious leadership. In 1904, the British colonial Government of India authorized the Younghusband Expedition, a military invasion of Tibet ostensibly designed to prevent the Russians from taking it. London disapproved of the move and the following year Younghusband’s forces withdrew.

Among the Tibetans the incident provoked

outright rebellion against anything and anybody foreign. In 1905 a widespread uprising began at Batang

in southwest Sichuan, where the lamas instigated attacks on the foreign

missionaries, all their converts and Chinese government officers. Victims suffered grisly deaths, especially

the priests, and the rebellion spread to Litang and Kangding in Sichuan and

down into Yunnan in Atuntse/Deqin.

Massacres of priests and their followers took place in Deqin and Cikou,

the French mission in the Lancangjiang valley south of Deqin. Marauders mounted the severed heads of the

priests on the Dechenling Monastery gate in Deqin.

Chinese government forces halted the rebels’ advance on Xiaowieixi, the next Christian settlement south of Cikou. They then marched on Deqin, isolated and surrounded the lamas in Dechenling and finally slaughtered everybody inside and burnt the building to the ground. Chinese officials took charge of the administration, but eventually married local women and stayed on after their service was completed. Surviving Christians rebuilt their demolished church in Cizhong, a little north of Cikou, this time in a French village style.

The main reason travelers go to Deqin is not for the city’s few attractions, but for the view of the nearby snow mountains. On a clear day this is truly magnificent. Leaving Deqin the road heads towards the Lancanjiang and after climbing out of the city’s valley and into the countryside, doming to Dong village and the modest Feilai Temple, surrounded by grain fields. Inside the main hall is a large statue of the mountains’ guardian deity. In the annex, when I visited, the carcasses of freshly killed goats hung from the rafters. As the monks were presumably vegetarian it wasn’t their food. Some Bon, pre-Buddhist sacrifice? I wondered, but never did find out.

Lovely Taizishan Snow Mountain, 6054 meters altitude, is visible from the approach to Dong. A little further on, at a small break in the forest, is the most celebrated viewpoint. Looking west one can clearly see Meili Snow Mountain, at 6740 meters altitude the highest in the province. From its peak a long wide glacier runs down in front. This is the most accessible glacier in Yunnan and in later years tour companies promoted one-day hikes to it and back or overnight camping at the glacier’s foot. Adventurous travelers could also go on extended treks in the nature preserve around the mountain.

On my visit the viewpoint also featured

several chortens and strings of prayer flags, adding a religious aspect

to the scene. After a few years the

government built a high wall between the road and the viewpoint with a ticket

booth in front of its only door. The

entry fee was 150 yuan. On my

visit it was free.

The road continues along the

Lancangjiang Valley all the way to the Tibetan border, passing both forested

and barren areas and through tunnels chiseled out of the cliffs. It is a good example of Yunnan’s road

engineering skills, though occasionally subject to landslides, which are always

quickly restored. Herder take their yaks

along the same road and wherever fatal accidents have occurred, people have

erected chortens on mounds of stone slabs inscribed with Tibetan

prayers.

About 30 km north of Deqin the road swerves away from the valley to cross the Adong River. Upstream stands a major hydroelectric plant and a switch pulled here daily around midnight plunged Deqin and vicinity into darkness. Further up, 64 km from Deqin, lies Foshan, a nondescript town from where the Lancang River is the provincial boundary between Yunnan and Tibet. Just past Foshan is the rather prosperous village of Nagu, famous for the ancient stone coffins found nearby, but unfortunately they had been removed to a museum by the time of my visit. Another 40 km is the Tibetan border, with an old Naxi settlement on the way, a relic of the early Qing Dynasty when Naxi troops from Lijiang guarded the border.

While the mountains south of Taizishan are not as high or dramatic, the scenery all the way to Cizhong is quite impressive. A road from the south end of Deqin winds along narrow gorges cut by the Lancangjiang’s tributary streams, offering sporadic glimpses of the snow peaks, passes through three tunnels and then makes eight distinct bends on the descent to the riverside town of Yunling.

From Yunling the road runs along the

Lancang River, with excellent views across to isolated villages, monasteries

perched atop ravines, deep gorges cut by streams, splendid tall, thin

waterfalls spillling over sheer cliffs, and occasional thick forests that burst

into a variety of colors in autumn.

Around Yanmen, 30 km south of Yunling, Nagu-like stone coffins have also

been found, including remnants of ancient pottery and bronze artifacts.

A little downriver on the opposite bank lies the county’s last major attraction—the Catholic Church at Cizhong. Tibetans comprise 3/4 of the population, with Naxi at 20% and Han 5%. The altitude is sufficiently lower here so that Cizhong farms can grow rice instead of barley. Viniculture, introduced by the French missionaries, is also prominent and Cizhong has a reputation for its wine. Tibetan Christianity never revived in Deqin, but here in Cizhong, in spite of 1905, it survived. Its congregation is mostly the older generation, but its very existence puts Cizhong on the list of what-to-see for any traveler seriously exploring Deqin County.

No comments:

Post a Comment